But the mythology of failure persisted and Clough found himself transmitted to posterity as a minor moon in Arnold’s orbit, a useful illustration of everything his friend thought amiss with modernity – its absence of heroic action, its subjectivity, its fragmentation and confused multitudinousness.

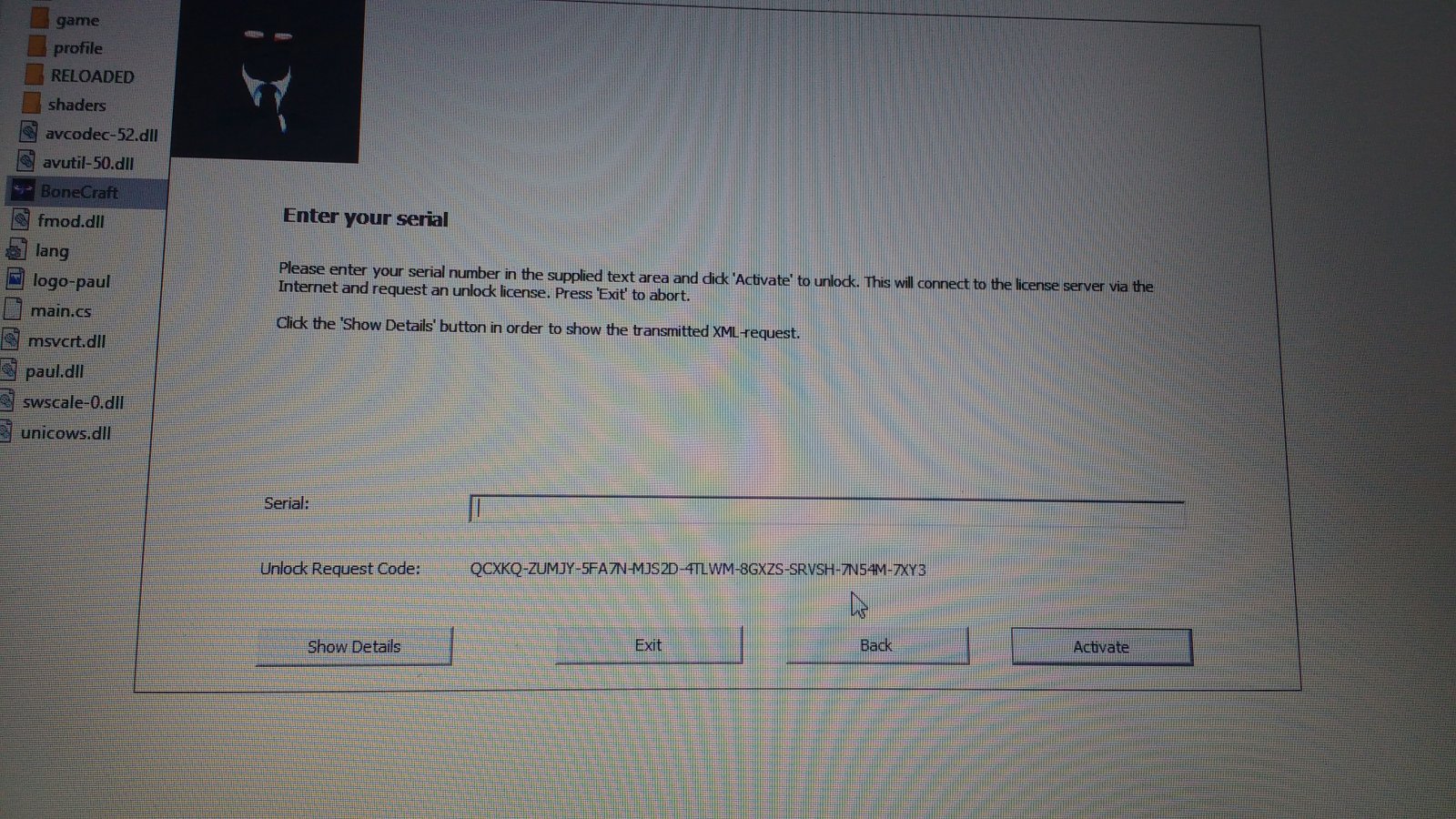

#BONECRAFT SERIAL FULL#

The full range of his poetic activity became clear only after his death: two blazing unfinished verse dramas, Adam and Eve and Dipsychus and the Spirit a fantastically spiky novel in verse, Amours de Voyage (in his lifetime published only in America) a Chaucerian collection of verse tales told by the passengers on a transatlantic steamer, Mari Magno and a welter of more or less polished lyrics. Though his biographers have never been able to decide whether Clough was an utterly singular or thoroughly representative figure (Mr Mid-Victorian Doubt), as a poet his place has proved stubbornly marginal. ‘I had long a foreboding something was deeply wrong with him.’ ‘I cannot say his death took me altogether by surprise,’ Arnold confided to a friend. Only they never do appear.’ Clough’s premature demise seemed in keeping with this general impression of hopelessness. Lewes wrote, ‘one of that class whose unwritten poems, undemonstrated discoveries, or untested powers, are confidently announced as certain to carry everything before them, when they appear. ‘He was one of the prospectuses which never become works,’ G.H. His death in 1861 at the age of 42 elicited sighs over his ‘wasted genius’, ‘baffled intellect’ and ‘unfulfilled purpose’ from those who recognised the force of his talent – and bemusement from those who did not. Many years after he left Oxford people still knew him only as the author of half a volume of fiddly, soul-searching, at times deeply impressive poems characterised by moral austerity and expressive incontinence, and one politically feisty and unpronounceable narrative poem, The Bothie of Toper-na-Fuosich (1848), valued principally for its depiction of Highland scenery. Clough’s abortive career as an Oxford don and his perceived failure to make something of his gifts damaged his personal and literary reputation.

His father, a cotton trader, sent his two sons to school in England, and to Wales for the holidays. He was born in 1819 in Liverpool, though his family moved soon afterwards to South Carolina. The poems themselves are persistently drawn into this bind, counting the cost of submission and resistance: ‘What incense on what altars must I burn/And what abandon, what unlearn or learn?’ĭuring his lifetime, Clough was chiefly known for disappointing the expectations of his friends, many of whom went on to occupy high places. ‘You are too content to fluctuate,’ his friend and rival Matthew Arnold once rebuked him, ‘to be ever learning, never coming to the knowledge of the truth.’ As one of Clough’s most sympathetic 19th-century readers, the philosopher Henry Sidgwick, observed, he was a man who would neither ‘heartily accept mundane conditions and pursue the objects of ordinary mankind’ nor ‘reject them as a devotee of something definite’. ‘Mr Clough sat at the foot of my sofa with this keen expression of investigation, which I determined not to mind, & only thought him un-understandable.’ Part of what unnerved Clough’s contemporaries – in his verse as well as in life – was his talent for scissoring through the evasions and impostures of Victorian morality: ‘Thou shalt not kill but needst not strive/Officiously to keep alive’ ‘Thou shalt not covet but tradition/Approves all forms of competition.’ Just as unsettling was the sense that, despite his destructive energy, Clough never seemed to arrive anywhere. ‘I tried to talk with him, but he has the most peculiar manner I almost ever saw,’ she wrote to Thackeray the following day. I n the summer of 1849, Arthur Hugh Clough went to dinner with the writer Jane Octavia Brookfield.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)